How to Avoid 5 Key Investment Biases Using Behavioural Economics

In the actual world, behavioural economics combines elements of economics and psychology. It assists us in understanding how and why people behave the way they do. It is an investigation into what people “should” do, what they “really” do, and the repercussions of their acts.

It distinguishes behavioural economics from orthodox neoclassical economics. Traditional neoclassical economics implies that all humans make well-informed and rational choices. However, behavioural economics takes into account the emotional and impulse aspects of decision-making. It considers how humans are still influenced by their surroundings and circumstances.

The basics of behavioural economics from the perspective of an investor will be the emphasis of this blog. We will cover five investment prejudices and explain how to avoid them.

Availability Heuristics

It describes our proclivity to rely on unprocessed and readily available information. We employ such information since it is readily available to our thinking.

Take, for example, any film that features twins. They demonstrate that the twins are similar in every way. They are revealed to have the same facial features, clothing, and behaviours. It has an effect on people’s minds. People begin to believe that twins are always identical in all situations. Data suggest, however, that 20 to 25% of twins are identical. Fraternal or non-identical twins make up the vast majority of twins.

Similar biases can be found in investment as well. Cryptocurrencies, electric vehicles, interest rates, and other exciting and trending events influence our attitudes and choices. Investors believe that if something is in the news or attracting attention, it must be significant. They do not doubt the accuracy of the information.

Rationality with Bounds

According to the bounded rationality hypothesis, the decision-making process loses some of its rationality due to any of the following three factors:

a) When the cognitive ability is limited; b) when information is imprecise; and c) when time is constrained

When you order at a restaurant, for example, the waiter begins to hurry you. Because of the time constraint, your food selection decision will most likely be suboptimal. It is referred described as “bounded rationality” by behavioural economists. Almost every day, we see the investment version of it. Stock recommendations and intra-day calls issued by brokerages are used by investors to select equities.

It’s a classic example of the investor:

a) Limited information processing skills b) Inadequate research c) The fear of missing out (FOMO) factor

It forces the investor to make irrational decisions.

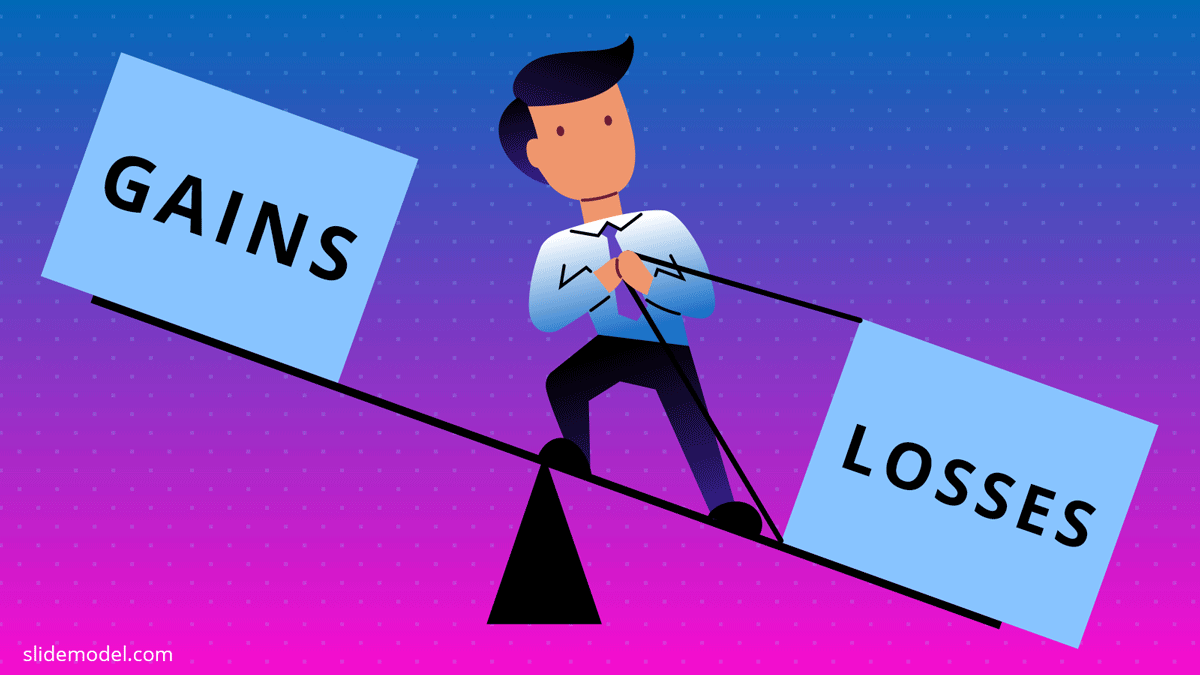

The Prospect Theory

According to this idea, investors view wins and losses differently. They frequently give more weight to perceived benefits than perceived losses. For example, suppose a person is given the opportunity to win:

a) Rs 200 guaranteed or b) a 20% chance of winning Rs 1,000 with an 80% probability of winning nothing

The majority of consumers will opt for the Rs 200 guarantee.

When the same individuals are faced with the following:

a) The first choice, which offers them an 80% chance of losing Rs. 1,000 and a 20% chance of losing nothing; or b) The second option, which gives them an 80% chance of losing Rs. 1,000 and a 20% chance of losing nothing.

Most people will risk losing Rs. 1,000 in the modest 20% chance of not losing anything at all. The preceding is a simple yet effective illustration. It shows that people are prepared to assume a higher statistical risk. They will do it if it means avoiding an Rs. 1,000 loss rather than an Rs. 1,000 wins.

Investors exhibit the same behaviour as described above. They will continue to invest in losing equities in order to average out the price. On the other hand, they easily book profits on equities that have increased in value over time.

Discounting via Exaggeration

.jpg)

Hyperbolic discounting behaviour refers to people’s preference for rewards that require a waiting period. It asserts that humans prefer modest and quick benefits over larger but delayed ones. It happens more frequently when the delay is closer to the present than the future. The preference for smaller and more immediate rewards appears to be logical. The second section is really intriguing. Consider the following two scenarios:

Scenario 1: Study participants were given two payment alternatives. Choose between an instant payout of Rs. 5,000 and a payment of Rs. 10,000 after one year.

As expected, a sizable percentage of participants chose the Rs. 5,000 quick payout option.

Scenario 2: Two payment choices were presented to the same individuals. Choose between Rs. 5,000 after four years and Rs. 10,000 after five years. Many more people chose the Rs. 10,000 option. However, the time difference was still one year, as demonstrated in the first instance.

To put it another way, people avoid waiting more as the time approaches. It is another way of saying that individuals are impatient and favour short-term gains. However, over time, people grow far more patient and wait for higher benefits.

Many of us may be unaware of this in our daily lives. However, hyperbolic discounting occurs in a variety of contexts. Willpower failures, consumption choices over time, and, of course, personal money decisions are all part of it.

Accounting in the Mind

Mental accounting describes how people tend to attribute subjective values to money. It is determined by how the money is acquired, how it is supposed to be utilised, and how we feel about it.

You, for example, use your money wisely. Even for little amounts, you normally avoid ostentatious purchasing. But suppose you find a Rs 100 note on the street.

Will you keep the money, like you always do? Will you spend your good fortune on a snack and a drink at your favourite street food stall?

That Rs. 100 will most certainly make its way into your stomach within the following hour. It establishes a starting point. People place varying values on money received as pay, birthday money, annual bonuses, emergency capital, sanctioned loan amount, lottery winnings, and so on.

When an investor splits their portfolio, mental accounting manifests itself. The portfolio is separated into two parts: safe and speculative. It is understandable that this is done to keep any poor results from speculative investments from hurting the overall portfolio. However, the truth is that the investor’s wealth is the same. It will be the same as if they had combined all of their investments into a single larger portfolio.

The preceding section concentrated on five abnormalities or investment biases. The discussion of behavioural economics will continue in the following section. It will look at several ways that investors can adopt to avoid or reduce these investment biases.

Strategies for Overcoming Investment Biases

Begin with the availability heuristic. It is the behaviour that emerges from the numerous shortcuts that our brain takes in order to digest a large amount of information.

System 2 Reasoning

System 2 thinking can help you overcome or at least mitigate this prejudice. System 1 is quick and easy to use. However, System 2 thinking is a deliberate, thoughtful, and reflective approach of making decisions. According to System 2 thinking, before making a major decision, one should always take a step back. It ensures that there is nothing in the way of distorting one’s view.

When it comes to investment, thoughtful and reflective thought can involve things like:

When making decisions, consider base rates and probabilities. b) Consider the impact of trends and patterns.

c) Recognizing outliers and unpredictability d) Seeking a second opinion before making a conclusion e) Going back and revisiting any old material that can support or refute a decision

Pre-commitment

Pre-commitment is really about making it obvious to oneself:

a) What are your objectives?

b) What is your strategy? c) What are you committing to?

The more exact you can be with this, the more effective your journey will be.

It does not have to be a complicated procedure and can be completed with simple promises such as:

a) Every month, I will put Rs. 5,000 in a Flexi-cap fund.

b) I will rebalance my portfolio once a year on January 1st, etc.

Self-sufficiency is an excellent method to combat biases and temptations. It is widely considered as a primary source of long-term wealth growth.

The Push

A nudge is a method of affecting people’s choices in behavioural economics. It is accomplished by directing them to make specific decisions. Placing a fruit basket at the office cafeteria’s cash register, for example, is a great nudge. It persuades consumers to choose healthier foods.

Nudges, on the other hand, are never coercive. Thus, prohibiting junk food or punishing people for not choosing healthy options is not a nudge. To have the most impact, a nudge should be integrated easily into the environment.

So, what constitutes a nudge in terms of investment?

Setting up SIP instalment deductions between the 1st and 5th of the month is one example. It ensures that investment objectives are prioritised. The remaining funds can then be spent on both essential and non-essential products.

Similarly, when one invests in ELSS funds, the product functions as a nudge by reducing the likelihood of redemption. It ensures that the funds have at least three years to work their magic.

Thinking Critically

The phrase “critical thinking” may appear ambiguous at first. It simply implies being objective, impartial, open, and sceptical.

We must not rely on or base investment decisions on the first accessible facts, according to critical thinking. Instead, take the time to undertake the extensive study. They should look for any flaws in a fund, firm, or product. It provides the investor with a far larger picture of the canvas.

Questioning the optimist and pessimist leads to healthy scepticism. It can help us get closer to the truth and make better investment judgments.

It is necessary to keep an open mind. It ensures that the investor is not emotionally invested in a stock or the fund manager. Being open makes an investor more receptive. The investor should make the necessary portfolio modifications. They are affected by changing personal and external circumstances.

The Mindset of a Beginner and Teamwork

The Japanese term “shoshin” refers to beginner’s thinking. “There are numerous possibilities in the beginner’s thinking,” Shunryu Suzuki said. In the expert’s mind, there are few”.

A beginner’s mind is free of preconceived notions. It indicates it is not constrained by logic. It has far more possibilities than an expert’s mind. Furthermore, a beginner’s thinking is typically not conflicted in seeking assistance. Working in a group or as part of a team is a great method to overcome limits and propose a superior answer.

This manifests itself in the form of:

a) Educating oneself through books, newsletters, YouTube videos, and so on b) Participating in mastermind groups where people debate investment c) Using the services of a financial advisor, and so on

How to Become a Better Investor

This blog has addressed several ideas and tactics for avoiding the following five financial biases. As an investor, you can utilise them to mitigate some of the biases associated with behavioural economics. They frequently appear in our daily lives as well as our investing path. The more individuals recognise and handle these, the better the quality of their investment and other decision-making will be.

- Home Equity Loans vs. HELOCs: Which is Right for You?

- Top Personal Loan Providers in the United States: Rates and Benefits Compared

- Student Loans in the UK: Best Options and How to Apply

- How to Qualify for a Home Loan in France: A Comprehensive Guide

- Understanding Insurance Deductibles: A Comprehensive Guide

- Insurance Strategy 101: How to Protect Your Assets and Minimize Risks

2 Comments